By Ruth Ann Ruiz

The Post Newspaper Features Editor

Juneteenth, a federal holiday honoring the end of slavery in the U.S., originated in Galveston Texas and the intention of one day hosting a Juneteenth Museum on the island has been on the minds and in the discussions of people for many decades.

“Back when I was a young adult in the late 60s, we were talking about one day having a Juneteenth Museum in Galveston,” shared David O’Neal, a board member at Old Cultural Center in Galveston and a trustee on the Galveston Independent School Board.

The question of where a Galveston-based Juneteenth Museum should be located has become a bit contentious.

Sitting north of the newly renovated Kermit Courville Football Stadium is an entire city block owned by GISD.

The land across from the stadium is covered with grass and is fenced in. There are two openings in the northern portion of the fence. It appears empty, as though it has no purpose.

But appearances can be deceiving.

O’Neal explained the lot’s purpose is to serve as an open green space for children to enjoy freely, and it serves as a parking lot for many school districts and island functions.

“The lot is used as a practice park for soccer, football, frisbee, exercising and walking dogs and it accommodates 125 cars for parking during football games and other events,” O’Neal shared.

At one time the land hosted the Brooker T. Washington School. The school, like many other buildings and schools on the sand barrier island, was demolished.

There is a growing movement to use the empty lot as a location for the Juneteenth Museum.

“There’s something special about that block. The neighborhood holds a lot of history for Black people,” explained Sam Collins III, president of the Juneteenth Legacy Project.

The land is situated between 27th and 28th Streets, which lead up to the seawall. At one time, the only area where Black people were allowed to enjoy the beauty of Galveston’s beach was on that small stretch of sand between 27th and 28th streets, according to both Collins and O’Neal.

To the north of the stadium at 2627 Ave. M is Old Central Cultural Center. Before being the site of the Old Central Cultural Center, the address was one of the locations of Texas’ first Black high school. The building also once served as a library in Galveston where Black people were allowed to enjoy being library patrons.

Next to Old Central, at 2601 Ave. M, is Jack Johnson Park, named after Galveston’s native-born World Heavyweight Boxing Champion John Arthur “Jack” Johnson. The park was dedicated on November 13, 2012.

Within view of the empty lot, on Avenue L, is the historic Avenue L Missionary Baptist Church, which was founded as the first African American Baptist Church in Galveston before Texas was a state.

Kermit Courville Stadium has its own history as the place where many Ball High School football games and other school events have taken place since 1948.

There is no disputing the historic value of the area. The question is, will the lot one day host a museum that reflects the history of the neighborhood or be retained as an urban green space?

O’Neal and Collins are passionate about their stance. O’Neal feels it’s important to keep a green space within the urban area of Galveston, and Collins feels it is important to have a new building honoring the history of Juneteenth in a neighborhood filled with Black history.

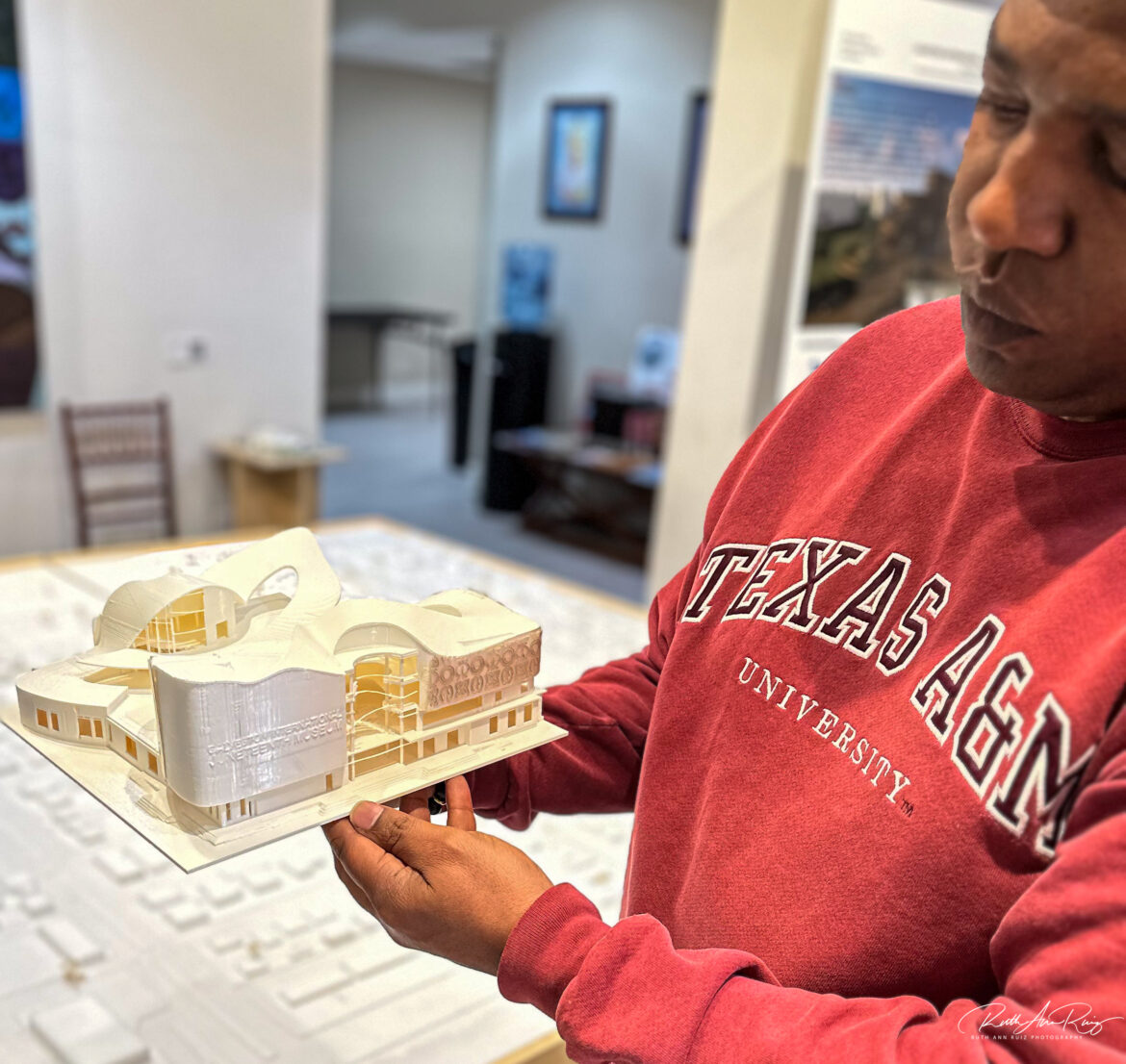

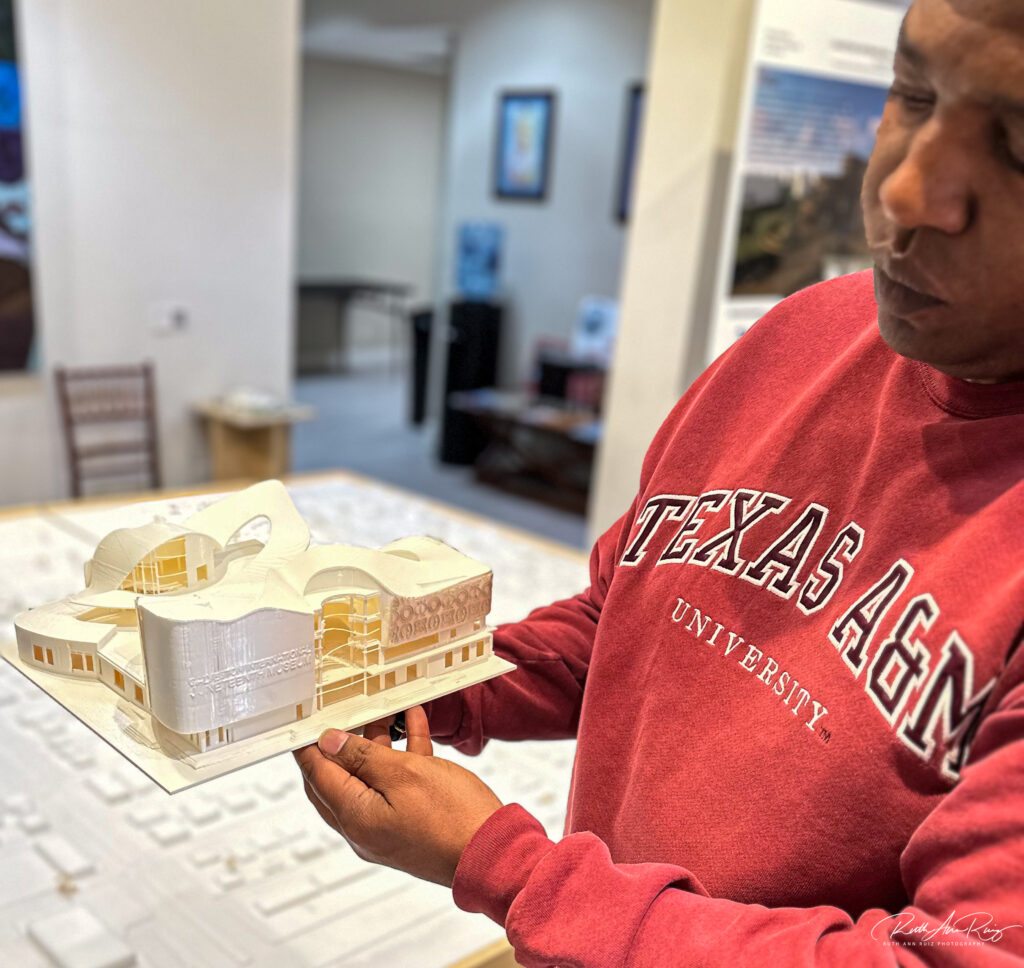

Architecture students from Prairie View A&M donated their skills to create several renditions of a new state-of-the-art museum building that would fit on a lot the size of a city block. The student renditions were open for public viewing at the Nia Cultural Center, and the public was invited to vote for their favorite rendition. The final vote came for a design that has been affectionately named “The Black Butterfly.”

According to Collins, the elected building design incorporates 60 parking spaces that would be available for school district functions. Collins envisions cooperation between the school district and the museum for many future events.

If the school board does not want to lease the land for the building of a Juneteenth Museum, that won’t discourage efforts for building a Juneteenth Museum in Galveston.

“We’ll build it somewhere else,” Collins said when asked what would happen if the board said “no.”

O’Neal feels there are several other options in Galveston that might be ideal places for a new state-of-the-art building that would host Galveston’s Juneteenth Museum while still allowing the land near the stadium to remain an open green space.

Both O’Neal and Collins are in agreement, a Juneteenth Museum is needed in Galveston, and both are eager to see this desire to honor history come to fruition.

Once the decision is made as to where to build a Juneteenth Museum, the next step is to work on fundraising for it.

Collins is confident there will be sources for funding the museum once the project gets over the initial hurdle of determining the museum’s location.