By Vera Bell Gary, Direct Descendent of Calvin Bell

The Emancipation Proclamation was issued in Washington, D.C. in September 1862. On June 19, 1865, U.S. Major General Gordon Granger marched into Galveston at the head of 2,000 Union Soldiers. He issued General Order No. 3, informing Texans that President Lincoln had freed the slaves two-and-a-half years earlier. General Order No. 3 Notified Black Texans that what Lincoln had promised them years earlier had come to pass.

General Order No. 3 states that the people of Texas are informed that in accordance with the Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. That involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness there or elsewhere. Absolute equality is not about equal results, but about creating an environment where each individual can become their absolute best without hurdles or barriers stopping them.

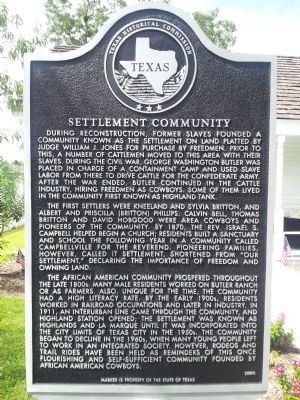

The roots of the Settlement date back to an 1864 Labor Containment Camp on Clear Creek in North Galveston County for impressed slaves and free Black people during the Civil War. After the Civil War in 1861, Judge William J. Jones set aside 230 acres, the only land in the county available for purchase by freedmen who could get testimonials from local businessmen proclaiming their good morals and work ethics, and in what would become the Settlement community. The community was originally known as Highland Creek and as Buttermilk Station. In 1890 its residents learned of another Mainland Community of the same name, so, Madam St. Ambrose, Post Masteress, chose the name of La Marque, which in French means “The Mark”.

The 1867 Settlement was established and grew after the Civil War. Many of the initial settlers had worked for George Washington Butler (a slave owner) as cowboys on the Chisholm Trail. George Washington Butler owned longhorn cattle by the thousands and had plenty of cowboys to work and drive cattle up the dusty Chisholm Trail between League City and Kansas to market. George W. Butler treated his slaves well and with his help, four of his slave cowboys who worked the Chisholm Trail were paid $1.00 a day, 50 cents more than cowboys working other herds. These four enslaved Chisholm Trail cowboys, Calvin Bell, Thomas Britton, Thomas Caldwell, and David Hobgood earned money herding cattle. They used their stakes to buy property and build homes for their families. The work allowed the men to establish a church, a school, and a post office. The four freed slaves made an indelible mark upon Texas history by building the only Reconstructive-era, self-sustained African American community in Galveston County. The Settlement boasted an 88% adult literacy rate, and the majority of its residents were landowners.

The 1867 Settlement is the oldest Reconstructive-era African American community in Galveston County. It was an independent community of African Americans established after the end of the Civil War. The community was located on 320 acres in Galveston County, Texas, near the Galveston, Houston, and Henderson (GH&H) Railroad. It was an incorporated residential community on Highway 75 (now Highway 3) and Farm Road 348 (now FM 1765). The community centered on Bell Drive just off of FM 1765 and Highway 3. Texas City corporated the incorporated section of La Marque on September 9, 1953. They annexed the land once called the Settlement. The incorporated area was pretty isolated until the early 20th Century when the Galveston-Houston Electric Railroad built a station in 1911. The electric-interbon train track between Houston and Galveston was constructed through the middle of the Settlement. By 1920 the community featured a Masonic Lodge, a hotel, and a restaurant. Its children had access to the government-supported school, the La Marque Colored School. In the 1920’s, its population more than doubled. Many of its workers abandoned farming jobs in favor of industrial work at nearby plants in Texas City.

In 2010, the 1867 Settlement Historic District was added to the National Registry of Historic Places, making it the only Reconstruction-era Historic District in Galveston County, Texas. Markers have been placed on historical sites throughout the community. The oldest structure, the 1867 Frank Bell, Sr. and Faville Bell home was restored as a Community Museum and was donated by the Bell Family to the City of Texas City in 2012.

In 1878, Calvin Bell registered his own cattle branding iron in Galveston County, Texas. Its artifact is on display in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture as part of one of the inaugural exhibits in Washington, D.C. The branding iron, which once belonged to Calvin Bell, was personally donated, and delivered to Washington, D.C. by descendants, Erma Johnson, Felicia Taylor, Delicia Taylor, Katherine Taylor, and Ronald Johnson (the family of Mary Ann and Walter Bell).

In August 1996, a historical marker honoring Frank Bell, Jr. was unveiled and dedicated at the La Marque City Hall located at the corner of the parking lot, corner of Cedar and Bayou. The marker details Bell’s achievements as a civic leader and a partner in the real estate company that developed the Carver Park neighborhood of West Texas City.

Frank Bell, Sr. was a slave of Mr. Henry Martin Stringfellow of Stringfellow Orchard (on Highway 6, Hitchcock, Texas). Mr. Stringfellow valued him so much for his work in the orchard that he mentioned Frank Bell in his book. He also apparently paid Bell and other workers $1.00 a day in the 1880’s and 1890’s, when others were only paying 50 cents a day.

In 1938 Lincoln School was built in the William Bell Subdivision, part of the Kneeland and Sylvania Britton’s tract of land bordering Bell Drive and Carver Street. In 1956, a new auditorium was built for Lincoln School, and later a gymnasium. In 1952 Woodland School was built on Carver Avenue in the Pollitt Subdivision directly across from Lincoln School. (Dolly Pollitt was Kneeland Britton’s daughter.)

In 1948, the Bell, Armstrong, Patrick (BA&P) Realty Company sold 20 acres and donated five acres of land to Galveston County for Carver Park, the first African American park on the Galveston County Mainland. BA&P Realty Company built a new housing development adjoining the park, Anderson Street, Woodrow Street, and Park Street.

In 1950, Bell’s Chapel Church congregation built a new church building on Carver Avenue in the old Thomas Britton tract. The congregation changed its name to Greater Bell Zion Baptist Church.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 initiated profound changes in the Settlement’s way of life. Since 1867, the self-sufficient African American community had continued to grow and prosper until the late 1960’s when segregation largely ended. The Settlement, now a part of Texas City, is a place tied to its roots, a place where a horse or two can still be seen on every block.

The residents of the Settlement pulled together, creating all the elements necessary to survive and thrive for the next century as a self-sufficient community until its incorporation into the city limits of Texas City.